The FRQ is a significant portion of final ap scores, but possible flaws raise concerns.

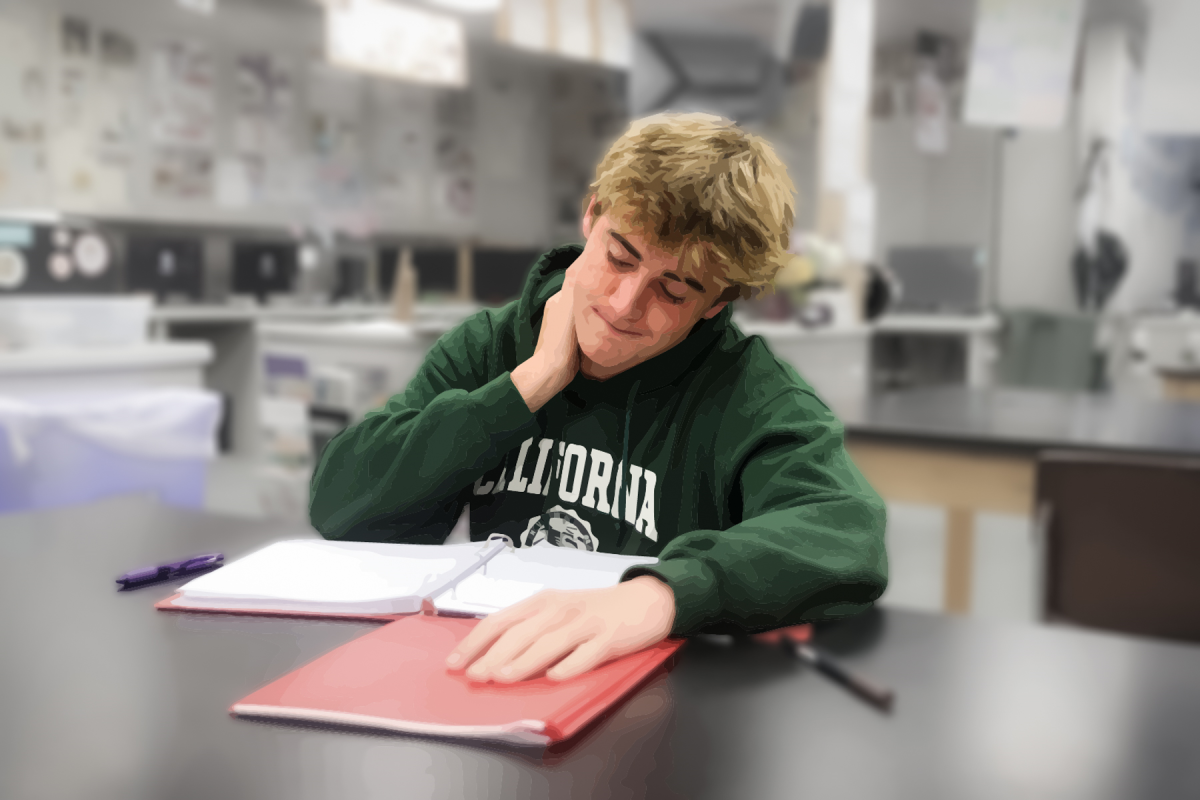

It’s happened to everyone: you write an essay you’re sure is better than the person sitting next to you but somehow your score is lower. You may be left wondering how accurate the scoring really was. If you’ve failed an AP test you’ve probably had the same thought of How accurate is this unseen grading?

AP tests have become a staple of the honors highschool student experience with over four million tests being administered annually, but the FRQ section of the test has caused confusion in some students. With some qualifications for points being as vague as “demonstrates sophistication of thought,” worries arise on the subjectivity of these measurements.

AP Cohort Data reports 1,178,256 public high school students from the class of 2021 took 3,980,474 AP Exams, with over a third of all public high school students from the class of 2021 having reported taking at least one AP exam throughout highschool. Yet only 22.5% of these students reported having passed at least one AP exam.

AP tests are graded by trained paid volunteers, often college faculty or high school AP teachers during a week-long “grading camps,” wherein they assign scores for free response sections of the tests. Those scores are combined with the Multiple Choice portion of the test, scored electronically, and the “Chief Reader,” appointed by the College Board, will meet with the members of the Educational Testing Service to decide what raw scores correspond for each final number grade. The cutoff is based mostly on previous years’ scores and how other students did.

The percentage of the score based on free-response questions varies, but is estimated to be on average a third to a half of a student’s grade.

Each AP test is scored from 1 to 5, low to high. A 3 is considered passing, and many universities will count 4s, 5s, and occasionally 3s for college credit, though the system varies greatly depending on what college you attend. The Princeton Review notes that many high ranking colleges consider 5s eligible for college credit and count a 4 for nothing, functionally meaning the scores often define what classes one will take in college and, in the case of students who take multiple AP exams, whether or not they can graduate early.

AP English teacher and former AP test grader Aaron Cantrell displayed faith in the AP test system claiming, “They will be correct within a single point score of the actual grade… they know what they’re doing.”

To test the efficacy of the AP test scores we reached out to several AP test graders and had them grade two similar essays. The content of the two essays was identical; yet one was written in clean handwriting with no crossing out or mistakes in the writing process, while the other was written more messily but still legible handwriting including several cross outs and text alterations via arrows or carets pointing new words into the text.

All tests were scored within the one point score of the “actual grade”. One point can be the difference between passing and failing, saving thousands of dollars by getting college credit or not, a domino effect caused all by a single inconsistency.

Possible problems in the experiment exist, with small sample size may have hidden a larger possible gap in grading errors, and a lack of “handwriting expert” meant that if the handwriting was beyond interpretation, the score might be lower than they would give in the grading camps.

Ultimately however, the point for many still seems to be that the system in which the tests operate is flawed.

In an article in the UnDark online publication, a former AP grader pointed out the aforementioned domino effect in how a single point of difference, and usually one based in some subjectivity, could mean the difference of getting into certain colleges, receiving college credit. She noted inconsistencies in grading in terms of the ever-changing rubric, and how, in terms of science tests, correct answers can be found outside what the rubric outlines and still be points off- unless, that is, the leaders add new criteria to the rubric as a response to grader concern, thus resulting in higher scores as the week goes on- something they reported anecdotally as she aren’t allowed to disclose exact numbers and scenarios.

She maintained that the test is very important and the least College Board could do is “give a fair shake” to everyone, suggesting additional care in grading and allowance for revisiting of grades.