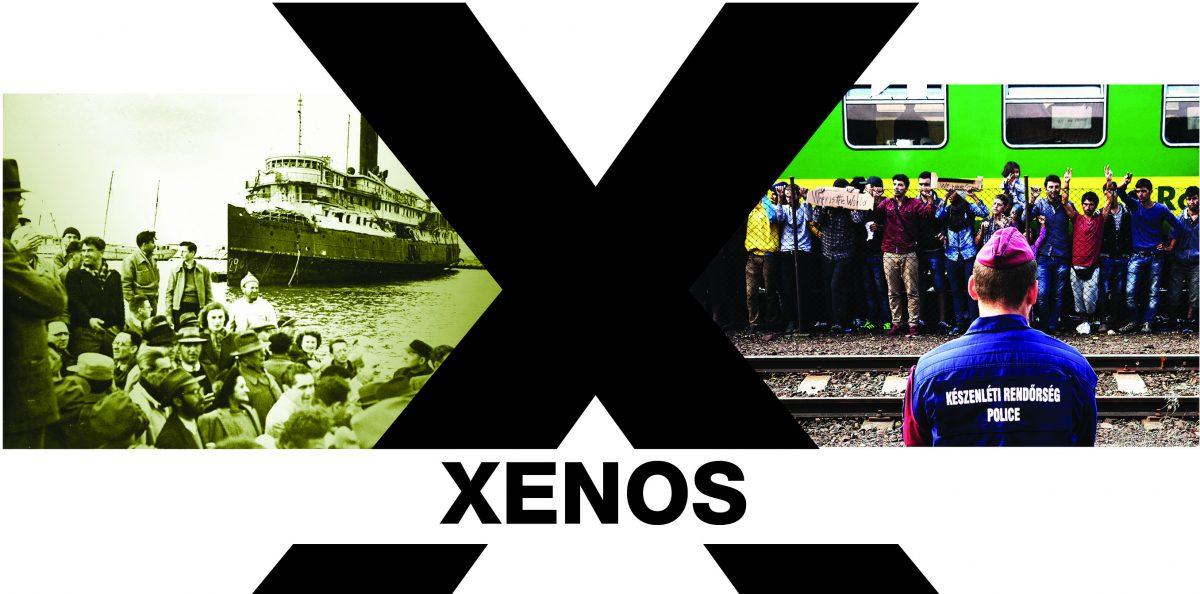

Meaning: stranger, enemy, guest friend, and family

Xenos. It’s one of the most complicated words in history, for one of the most tangled topics in history. Because Xenos can mean stranger. It can mean enemy. It can mean “guest friend.” Or it can cover the entire topic of Greek hospitality, and the idea that spans the entire course of human history. It means help, safety, sanctuary, friend, and family.

Xenos can mean welcoming foreigners into your home and treating them like family. It’s an ambiguous word on purpose because humans have always been divided on the issue of offering their own homes, earnings, food, and families to strangers.

The Syrian refugee crisis–and the exodus occurring out of many Middle Eastern countries–once again raises the virtue of Xenos before politicians and citizens .

Xenos always comes down to the issues of trust and generosity. It is a risk, certainly. It asks hosts to humble themselves, change routines, and give. It simultaneously asks guests to respect the house, tread gently, and contribute what they can.

Now where has that ideology gone? It has disappeared into a vast library of literature and ideas, shelved snugly between Plato’s allegory of the cave and Steinbeck’s concept of “timshel.”

It is packed away, waiting for a society that gently will wiggle it off of the shelf, and blow the dust off, and crack open the spine of its doors and policies so that strangers can have shelter and blessing.

The refugees in Syria need the world and the United States. They stumble and flee a war stricken land. They are turning to the world, watching with anxious eyes, filled with the images of the horrors they’ve seen and the children that have died. They are looking for a sanctuary; they are looking for healing. They are looking for Xenos.

Some in the world are stepping up, Germany is accepting refugees by the thousands. Yet others are turning away from Syria, shoving away the old concepts that ruled in the ancient kingdoms as foolish, risky, and upsetting.

But Xenos also involves a potential mystery of fate, faith, and destiny. It is centered on the idea that any human could be a holy god. To mistreat anyone was a grave sin. The guest could have been a god or an angel. Xenos expected that the stranger was sacred, a person to be honored.

Xenos follows the small children from Honduras that cling to the top of trains as they are jolted down to the path to what they hope is a better future than the drug invested corrupted world that they have always known. These children are looking for help. They are looking for a family to take them in.

We must not raise walls and taxes to stop these refugees. We must not shove away the concept of Xenos because we don’t trust these people. We must not forget that we were once all immigrants in this land, struggling to survive, and welcomed by people who were worried about us. We were all once shown Xenos. It is what this country is built upon, but we have hurried past this, eager to argue that the immigrants are rapists and drug dealers.

And Xenos lingers at street corners and twists around people curled up on park benches. It dwells in the homelessness that we consider a plague, who are sifting through the uncaring masses for a friend.

In this world, this country, this state, this city and this school, we should pursue Xenos.In this country Xenos has become a form of weakness, a sign of stupidity.

We urge you to not let it become so. We have to create a generation that sees Xenos as not a thing of the past, but as the only way to a bright future. We must trust each other, no matter how difficult it is at the beginning. We must fan the flame, and create a society, where we don’t have to turn away orphans and families that have been torn apart. We must become a culture that believes in Xenos.