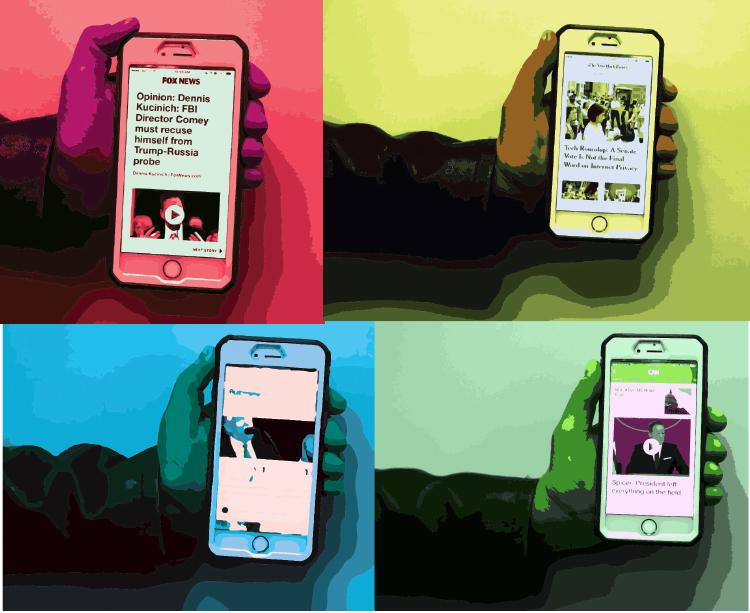

Let’s debunk popular misconceptions to lessen the political divide

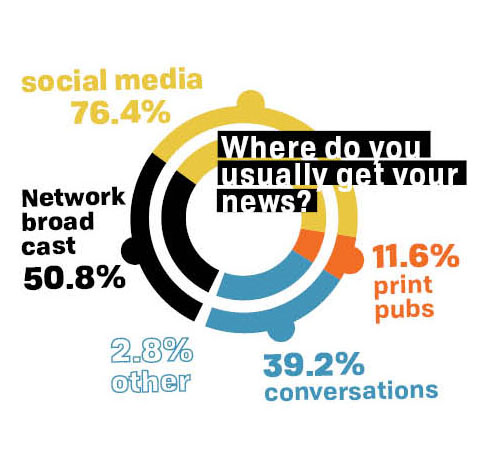

With fake news at an all time high, the media is essential to Americans’ news consumption. However, the tension between the political left and right is at a zenith in which politically leaning

journalism and audience commentology fuels news bytes everywhere. It is harder to discern what is honestly going on in the world—let alone our own country.

journalism and audience commentology fuels news bytes everywhere. It is harder to discern what is honestly going on in the world—let alone our own country.

“Vaccines can cause Autism.”

“Climate change is not real.”

“Hillary Clinton sold weapons to terrorists.”

“Donald Trump is promoted by the pope.”

These viral false narratives are at the forefront of our screens and have become the fodder for our arguments. The harmful ones need debunking. Society needs to understand its susceptibility.

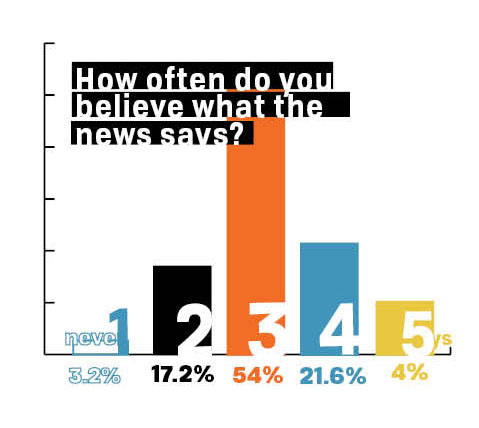

Rejecting information takes more mental effort than accepting it, according to research published by Stephan Lewandowsky of University of Western Australia. The intensity of recent political debates make it tempting to grab a hold of whatever information lends itself to your cause.

Even the best of the unbiased—and even we high school journalists at Crimson—have run into this impulse. It can be intentional, or simply happenstance, as choices are made about who and what to  cover, on what quote or fact to print or not. We journalists make these choices with the same dedication to our own personal beliefs that every other person possesses. In the search of the truth we are still biased humans; we want to believe whatever brings us comfort or ammunition.

cover, on what quote or fact to print or not. We journalists make these choices with the same dedication to our own personal beliefs that every other person possesses. In the search of the truth we are still biased humans; we want to believe whatever brings us comfort or ammunition.

But for the sake of journalism and of an informed civilized society, we need to set those feelings aside for the sake of fairness and a hunger for accuracy.

Imagine trying to do this on an international scale with every hot button topic known to man, and not within the happenings of a small town on the Central Coast. Around here, it is just plain hard

to remember which Facebook post is worth a grain of salt.

In the same Australian study, researchers presented people with a false news report about a warehouse fire caused by negligent storage of gas cylinders and oil paints. Later, when the participants read a retraction of the information regarding the cause of the fire, only about half of them reported that the initial account was wrong. This finding suggests that misinformation is still believed 50 percent of the time, despite the cycling of a correction.

“Is it the media that causes public panic?” nurse Kaci Hickox asked on Newshour. “Or is it that we, the public, just desire drama and fear—and that therefore feeds into the media?”

In short, we believe what we want to believe. We read what we want to read and the world caters to it.

It is not just about fake news or an expanding media’s newfound relevance in shaping our world. It is about conversations, or the lack thereof. It is about forgetting that your opponent is a person with the same biases and faults as you. It is buying into the sensationalism that has pumped off penny presses since the 1830s, and letting it warp our ability to tell if everything on the internet is true or not, and demanding more of it.

It is not just about fake news or an expanding media’s newfound relevance in shaping our world. It is about conversations, or the lack thereof. It is about forgetting that your opponent is a person with the same biases and faults as you. It is buying into the sensationalism that has pumped off penny presses since the 1830s, and letting it warp our ability to tell if everything on the internet is true or not, and demanding more of it.

Misinformation and heated disagreements are nothing new to us. They’ve just been reemphasized by current events.

A healthy study of at least three debated ideas circulating among students is timely and helpful: